About E.E. Cummings' Art

As a poet, E. E. Cummings has enjoyed tremendous popularity for nearly a century, and great critical acclaim from many different literary circles. His poetry has been widely hailed for its experimental form, typography, grammar, and word coinages, as well as for the subtlety and sensitivity of its perceptions and feeling. His nonfiction prose has been praised for its bitter wit and for the clarity and forcefulness of its expression, revealing Cummings as an intelligent, critical observer and chronicler of the modern, who, bound to no school of writing, expresses himself as an idiosyncratic individualist. His highly developed sense of the aesthetic was married to a deep skepticism toward that which was fashionable but uninformed by critical intelligence and the warmth of the human heart. Ezra Pound went so far as to place Cummingsʼ EIMI as the second most important book of the 20th century, ahead of James Joyceʼs Ulysses and second only to Wyndham Lewisʼs The Apes of God.

Less well-known, however, are Cummingsʼ achievements as a visual artist and the extent to which they express in an entirely different medium the same aesthetic principles and rigorous artistic intelligence that inform his poetry. Cummings viewed himself as much a painter as a poet, as evidenced by the enormous amount of time and energy he devoted to this lesser-known half of his "twin obsession." Not only did Cummings spend a greater portion of his time painting than writing, he also produced thousands of pages of carefully thought-out notes concerning his own aesthetics of painting: color-theory, analysis of the human form, the "intelligence" of painting, reflections on the Masters, etc.

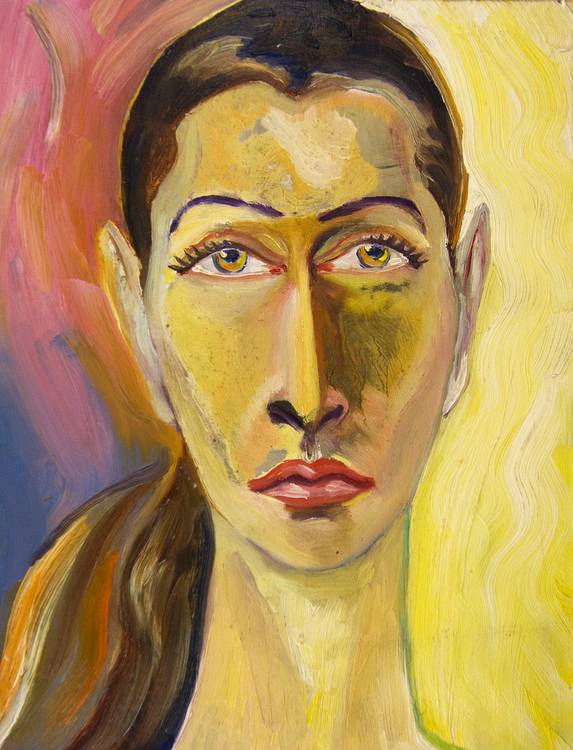

While Cummings achieved substantial acclaim as an American cubist and abstract, avant-garde painter in the years between the wars, he later viewed the artistic establishment as hopelessly anti-intellectual and dropped out of the New York gallery scene, devoting the remainder of his life to painting representational work: landscapes, nudes, still lifes, and portraits. In these works Cummings continued to explore the issues and elaborate the principles that had impelled his early abstract paintings, and he brought them to bear in his later, more personal, representational work. Indeed, he deliberately shunned avant-garde circles and the critics who validated them in favor of a more domestic or private environment in which to pursue his art and his continued inquiries into color, form, and feeling. Many of the paintings in this collection, while recognizable subjects, display a wild, exuberant, and sometimes nearly fantastic use of color. As such, they merit comparison with his poetry, the greatest accomplishment of which has long been considered his bold, inventive use of language and form in the service of a modern sensibility and aesthetic that is essentially individualistic, traditional, and even romantic.

Critics have tended to divide Cummingsʼ painterly career roughly into two stylistically differing chronological phases. The first phase, more or less from 1915-1928, covers his widely-acclaimed large-scale abstractions and his immensely popular drawings and caricatures published throughout the 1920s in the leading modernist journal, The Dial. The second phase, covering the period from 1928 until his death in 1962, consists primarily of representational works: still lifes, landscapes, nudes, and portraits. This dichotomy of avant-garde vs. representational in Cummingsʼ visual work has its parallel in a public vs. private dichotomy: above and beyond the popular Cummings-as-experimental-innovator of the first period, there is in the second phase the very much more private Cummings-as-aesthetic-sensualist, strikingly revealed in the wild explosions of color that are found in his landscapes and in the physical intensity of his erotic work. While the representational works are more traditional and accessible than his earlier abstracts, their use of color and form reveal a sophistication and development of technique fully as complex as the earlier work, if not more so.

When Cummings died in 1962, he left to his estate a large oeuvre of visual art, including oil paintings, watercolors, and drawings. The current collection comprises the bulk of the material he left at his death — a large number of pieces representing the width and breadth of Cummingsʼ visual output. Included are drawings dating back to his childhood, abstract oil paintings, circus drawings, burlesque sketches, visionary landscapes in oil and watercolor, erotic art, sensuous nudes, figure drawings, portraits of friends and family, as well as rare ink drawings documenting his travels abroad in the 1920s and '30s, a critical point in his development as a visual artist.

Cummingsʼ career as a painter, though less well-known than that as a poet, follows the same trajectory as his writing career and embraces the same sense of aesthetic values, from a willingness to be open and experimental, sometimes wildly so, to a nearly scientific rigor applied to the efforts to understand that which comprises aesthetic value and underlies all art. Cummings attempted to discover what would make a work of art not only pleasing and "successful" but also give it permanence, allowing it to transcend a given moment or a given "school" of art or thought and to touch that which is fundamentally human. An iconoclast and resolute individualist in both his poetry and his painting, Cummings consciously eschewed the favor of contemporary critics in order to pursue what he considered the more elevated course — the attempt to develop his visual art unencumbered by the trappings of any contemporary "school"; and he pursued this effort with a seriousness of purpose that belied some later critics' tendency to view him as a 20th-century American primitive: a subtle and sophisticated shaper of words but a visual artist whose subjects — landscapes, portraits, still lifes, nudes — became increasingly simple.

In this collection — the bulk of Cummingsʼ entire output of visual art over the course of a lifetime — the truism that "the whole is greater than the sum of the parts" is borne out in dramatic fashion. As Kidder points out, "[Cummingsʼ] sunsets, for example: seen as subjects are merely repetitious. Seen as experiments, however, they speak directly to his theories" about the relation of color to aesthetic feeling and experience. We see the experimenter both developing and testing his ideas about aesthetics and perception, in particular regarding the use of color. Far from being the "simple" paintings he was criticized for creating, Cummingsʼ representational work is the culmination of an entire life spent studying the nature of beauty and the human apparatus for perceiving, understanding, and expressing it. If this meant, as happened in his later life, that Cummings fell prey to critics who were unable to see beyond his choice of subjects, he willingly sacrificed the critical attention in favor of pursuing with integrity the artistic concerns around which he had focused his life — literature, painting, and even, to a lesser extent, music. As such, much light can be shed upon Cummingsʼ multitudinous notes and reflections on aesthetics and visual art by the examination of the actual "experiments" themselves — the finished works of art — and a re-evaluation of Cummingsʼ artistic accomplishments, unimpeded by the tides of critical fashion in his time, can be undertaken with a view to understanding, once and for all, the visual and aesthetic vocabulary of a man who is universally acknowledged as one of the great literary artists of the modern era.